theflightofthedishes.jpg

Dunguaire Castle, ‘the Fort of Guaire’ stands on a hill just outside Kinvara, County Galway. Surrounded by water on three sides it commands a fine view of the village, the Burren Mountains and the sparkling waters of Galway Bay. From minute to hour, sun and sky brings change to its walls and to the angles of its battlements. Dunguaire itself rests as constant as the mountains beyond. It’s a fitting seat for a King, and no less than five Kings of Connaught made their seat here.

It was a fitting seat for a King

The castle got its name in memory of the most famous one of all – Guaire. His reign was a time of plenty for the region. He served and protected all in his kingdom and he did right by them. He took from his tenants only what they could spare and ensured no person was left in need. He sheltered those who suffered loss or hardship, he made fair judgment in times of crisis and he treated nobleman and tenant with the same dignity and respect due all humanity. For that, he was much-loved. It was said he gave so generously that the giving caused his right arm to grow longer than his left.

One day, his dishes took flight..

Each time he sat down to eat he said grace. It was a simple entreaty and in keeping with his reputation as a benevolent ruler. “May the great God look down on us as we break bread together.” he would say. “And if any in my kingdom are more in need than I, then I pray they have this bounteous food to sustain them; and welcome.”

Those prayers were answered when, one fine day, his dishes took flight.

That wondrous happening took place within the banquet hall of Dunguaire Castle – around March or April some time back. It’s hard to be more precise, as it occurred over fourteen hundred years ago. What is known is that it unfolded some time during Easter Sunday. Back then, Sunday was, for all, a day of rest. Easter Sunday was particularly special. It marked the resurrection of the Lord and concluded many weeks of fasting for those who followed his teachings.

Neither man nor beast was safe…

On that Easter Sunday, Guaire and his troops were very much in need of rest and sustenance. They had spent long hours in the saddle the same day, hunting a ferocious pack of wolves that wreaked havoc in his kingdom. Guaire had kept track of them for years, respecting their free existence but, at the same time, making sure they did not encroach too heavily on his subjects or their livelihood. For their part, the wolves culled the old or the sick from herds and left well enough alone. It was a delicate balance and it worked, until a new leader ruled the pack and his arrogance caused disruption to this long-established tradition. Each wolf was the size of a small cow but the Alpha male, a huge grey, would put the fear of God in anyone. His jaws could fit the size of a small sheep and those jaws wanted the taste of young fresh prey, not the cast-offs from a herd. Under his leadership the pack grew stronger, faster and deadlier than ever before. They moved as one and thought as one and their victims rarely saw what hit them, which was a blessing. Eyes as yellow as molten gold and fangs the length of a maiden’s hand are not a pleasant sight, particularly if they’re directed at you. The animals were a scourge and neither man nor beast was safe.

It was a howl most horrible

Grey Wolf, Bavaria

Dawn had not yet broken that morning when the pack demonstrated the true level of their ferocity. A young herdsman was tending his cattle down by Cloonasee when a cluster of finches broke from the hazel, shrieking alarm. Seconds later a mute of hares exploded from the corner of field, followed by a fox who was more intent on outpacing them than having them for breakfast. The moonlight made silver ribbons of their tracks as they fled. The lad was no fool and he followed suit without hesitation, making for the hollow of an old oak as fast as his legs would take him, the hairs rising on the back his neck every step of the way. He was barely there when the Alpha sounded the attack. It was a howl most horrible. In seconds the pack breached the hill beyond Mountcross and bore down on his defenseless animals. In mortal terror, the poor boy watched as they cleaved a swathe of destruction through the innocent creatures.

Scarcely an animal was left standing

After the slaughter they closed ranks once more and travelled on through Shessanagirbe, a blur of black, grey and crimson menace. By the time the herdsman found courage to remove himself from his hiding place and seek Guaire’s solace they had ruptured the peace of Cartron, swung back across Cahernamadra and on to Roo where scarcely an animal was left standing. When they hit Aughinish the only hope left for those in their path was to swim out to sea. Cow, sheep and horse flung themselves into the wild waters of the Atlantic, followed by herdsmen in boats and in equal fear for their lives.

At his signal, they tore into action

Dawn had not yet broken

Guaire was incensed. While servants tended to the herdsman he readied himself for the chase. His best scouts rode out to track the pack. It was an easy task as the entire kingdom was in turmoil. The wolves had turned inland once more, heading for Carrowgarriff. Guaire called his troops, mounted his horse and set off past Doansheedy Fort at a full gallop. The King hoped that if he swung down by Shessareagh and around Caherawoneen south he might be able to get behind them. It was a hard ride but a solid plan.

The retinue came upon the wolf pack just north of Drumharsna near the old ring fort. Guaire directed his soldiers to form a half circle to the south, making sure to stay downwind. His warriors, trained as they were in the tradition of the Fianna, scarcely bent a blade of grass as they moved. Then, at his signal, they tore into action. With rí rá and ruaile buaile, with clamour and the clash of sword on shield, with every sort of noise possible for a human to make, King Guaire and his soldiers startled the animals into regrouping and forced them north. They sought cover in the woods of Rooaunmore, but Guaire gave them no rest.

Man and beast were glad to turn for home

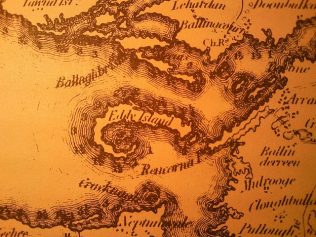

Island Eddy from Larkin’s (1818) map of County Galway

For many hours he chased them through track and copse, past tree and bramble, up hill and through turlough, cutting off their means of escape and directing their flight. He herded them through Kileenavarra and Ballymore, past Clough and Ballinderreen, and into Ringeelaun where they were finally cornered between shore and sea. The great grey turned to face them, ready for battle. But none was to be had. Guaire was not a violent man. Instead, he gave them choice. Either swim to Island Eddy and live there, or meet their end on the point of his sword. Naturally, they decided that moving to an island was the better course of action. And so they did.

The conflict was resolved. They had ridden for miles. Horses, troops and King were tired and very hungry. Their bodies were aching from the battle and the chase. Man and beast were glad to turn for home.

Threads of every colour were used in their creation

It was dinner time before they reached the badhún, or bawn, of Dunguaire Castle. The sight and smell of the place fair lifted their spirits. It was Easter Sunday after all, the day of breaking the Lenten fast, a day for celebration and feasting and preparations were well underway. The band dismounted and left their steeds to the care of grooms as they quickly made their way to the wash rooms. Scarcely an hour passed before they reunited to form a hasty trail up the winding stair to the banquet hall. They had donned their best attire, their finest brooches and their oldest crios. The crios was a woven belt used by Kings, warriors and all else for the purpose of holding up their trousers. Threads of every colour, including gold, were used in their creation, depending on the wealth of the owner.

Casks of mead stood in every corner

The reason Guaire and his warriors wore their oldest one was that this specific item of clothing was used as a measure of taxation. If a man got too fat for his crios, he was penalised for his excess by means of a levy. The heavier he got, the more he paid. It made sense to wear the oldest crios in the house to a banquet because age and wear meant they had a bit of ‘give’ and wouldn’t strangle its owner, or cost him money after a night of feasting.

In the banquet hall so much food had been laid out there was hardly room for plates. Every shelf and sill held bowls of smoked cheeses, roast hazelnuts, cockles and oysters. Vessels brimmed with honey beneath. Casks of mead stood in every corner, dishes of eggs and dried berries rested by every cup, breads and meats filled the space between. What surface was left held containers of the purest of water, the creamiest of milk, the smoothest of butter and the most fragrant of wine. The troops were assured of the finest of company of all in Guaire. As for himself, knowing their hunger, the good King barely let them settle before he entered. For that they were thankful.

All looked to their king…

To his left, two small windows overlooked Kinvara Bay

All bowed as Guaire took his seat on a throne befitting a man of his status. Huge tapestries adorned the walls, scored with images of his kingdom and conquests. To his left two small windows overlooked Kinvara Bay and village. At the other end of the room, opposite the stone arched entrance, a small stage had been prepared for musicians, sean nós singers and the seanachee. There was a fine bardic school over at Finavarra and Guaire was always spoiled for choice when it came to entertainment. The musicians were already in place, playing softly. The atmosphere was warm and all the more enjoyable after a long day. All looked to their king.

Bare miles away, another prayer was being said.

Guaire nodded graciously to the room and rose to speak.

“Today is a day for celebration.” He raised his glass. “Today the Lord has risen and for this we give thanks. This day also, my warriors, you have proven your worth. By the grace of God we have, together, ensured the safety of my kingdom and its people.” His troops saluted proudly. Their king bowed his head in thanks and concluded with his customary prayer. “May the great God look down on us as we break bread together.” He gestured to the food around him. “If any in my kingdom are more in need than I, then I pray they have this bounty to sustain them; and welcome.” “Amen,” echoed around the room. Seats clattered, lips were smacked and Guaire and his warriors settled with enthusiasm to the banquet before them.

The Burren is a place of contradictions

The stony place

Unbeknownst to all, at that exact moment, bare miles away, another prayer was being said. It came from – “the stony place” – the Burren – a landscape of swirling limestone and subterranean caves that run for miles through ungovernable soil and unforgiving terrain. Its wilderness of dips and hollows hold rocks that could take the leg out from under man or beast, or crush them to oblivion with one wrong step. The same grykes and crannies shelter the most succulent of grass and the most exotic of plants. It appears dry as a bone, yet conceals within itself springs of the purest and most refreshing waters. Though bleak in aspect, those familiar with its eccentricities can find shelter. The Burren is a place of contradictions, and no small amount of magic. You could lose yourself there, and you might well enjoy the experience.

He was ragged, unkempt and hungry

The prayers that rose from the heart of the Burren came from a hermit called Colman MacDuagh. Colman was brother to the King, though he could scarce be recognized as royalty. He had also finished his Lenten fast. However, his weeks of abstention were far stricter than those of Guaire and it had taken its toll on the man. He was ragged and unkempt, and hungry. Here in the heart of the Burren it was not likely his stomach would soon be filled, as all that was available to him was a small meal of plants and tubers. Colman did not mind such meagre fare, for he was a pious and holy man. It was, however, an entirely different matter for his servant. The young man had lost so much weight the bones were sticking out through his skin. He felt near death and he was far from happy that his last hours were to be spent in an alien and inhospitable landscape. In fairness to him, Colman was not blind to his servant’s condition.

The holy monk offered a heartfelt addendum to his prayers. “Let this poor child be fed, and fed well, if it be thy will.”

Colman’s supplication floated above the Burren and over the grey-blue limestone rocks. Onward and upwards it went until it met and mingled with that of Guaire. Both prayers were answered.

The windows blew open

Onward and upwards it went until it met and mingled with that of Guaires

Within seconds a strange turn of events unfolded at Dunguaire. The tables in the banquet hall began to shake. The huge tapestries billowed out like the sails of a ship, laying themselves over the heads of the diners. With a snap and a creak the windows blew open. Soft spring air floated in and around the hall. The air moved across the tables with a whisper, lifting Guaire’s cloak part-way over his face. The King’s crown slipped sideways and to the right, stopped only by the fortuitous placement of the royal ear. Sheets of music fluttered and wrapped themselves around the musicians’ heads. Servants covered their eyes as a blast of spices from a small bowl by the window scattered across their faces. The wind grew stronger. With a resounding clatter it blasted lids off every saucepan, tureen, bowl and pot in the room and bounced them off table, rafter and wall. At that point the servants didn’t wait for vision to return before they retreated, half tumbling over each other down the castle steps. Who would blame them?

It was a marvelous sight to behold

A marvellous sight to behold.

Through tangled tapestry, dangling tassels and watering eyes, all present watched in astonishment as each and every plate of food rose from surface, corner and sill around the banquet hall. Slowly at first they lifted, like they were testing the weight of themselves. A couple of eggs slid to the edge of a bowl. The bowl, sensing imbalance, righted itself in time to save its contents. So did the soup tureen, and a tray of lobster. One after another the plates got a feel for their journey and found confidence. With grace of movement platters of meats, breads and all else pirouetted over tables and across the room, to meet in its centre. More vessels joined the dance, and more. They melded together like a flock of starlings winding inwards and upwards towards the ceiling. It was a marvelous sight to behold. It was the Flight of the Dishes.

Every one of them got a bruise or a burn

First to react was Clare Bán, soldier of Guaire. She sat to the right of the King, and for good reason. She was the warrior of warriors, fearless, loyal, constant – and fast. Clare Bán leapt from her chair, grabbing for a plate of veal as it floated past her head. The platter shifted from her reach with such speed she lost her balance, toppling forward across an empty table. Without a bother the meat rejoined its companions in their dance. Tomás, sitting to the left of Guaire, grasped at a pitcher of ale. It dodged him neatly and he got a fine smack on the back of the head from a passing soup tureen for his troubles. Deirdre went for a bowl of scones. She secured a handful of air and a dash of piping hot gravy over the back of her hand. Eoghan seized a salver of hazelnuts. They flew off the bowl and scattered across his head before returning to their floating container.

Soldier upon soldier rose to save their dinner and each and every one of them got a bruise or a burn in return. Guaire himself grasped the tail end of a particularly fine joint of beef. He received such a clout from a skin of wine it put him over the back of his throne and nearly into the fireplace. It was only luck that saved him. And all the while the victuals continued to rise like a column of smoke to the ceiling. Amidst the confusion, one thing was certain to all present. That food wasn’t inclined to be eaten. Worse still, it started to arrange itself into two wedge shaped formations just under the roof, the points of the wedges directed at the open windows of the banquet hall. There was only one conclusion to be drawn from that configuration, and it did not bode well for their dinner.

“Rise! The windows!” Close the windows!”roared Guaire.

Warriors flew to do the King’s bidding but the fallen lids got a second wind. They rose again and shot across the banquet hall in the direction of the soldiers. The walloping they secured left them in a dazed heap on the floor, half blinded by crumbs, sauces and garnishes to boot.

As for the dishes – they had flown.

Hounds were summoned, weapons strapped, girths tightened

The dishes skimmed the triple ramparts of Rath Durlais.

The dishes made a wide circle around the back of Dunguaire. Skimming the triple ramparts of Rath Durlais they continued over the hill to Tobarmacduagh, up the side of Foy’s and across to Seapark House where they paused. By that stage Guaire and his troops were down the stairs and running towards the bawn shouting for horses. Hounds too were summoned, weapons strapped, girths tightened. With grim faces under stern brows the retinue mounted – and the plates returned.

They hovered, suspended by some miraculous force some thirty feet above the bawn. A small drip of honey broke loose from among them and with a soft plump, it landed in a spatter right between Guaire’s eyes. For a brief moment the King thought his dishes had got over their moment of madness and were settling to land. But he was wrong. That little jaunt around Dunguaire was only to test their potential. They rose as one like a flight of swallows, formed a large V over the battlements – and off again with them – straight towards Kinvara.

St. Coman’s bell rang of its own accord

The thunder of hooves was such it rang the bell of St. Coman’s

“Onwards! Onwards!!” roared Guaire spinning his horse in their wake. With a thunderous roar, thirty sets of hooves clattered and sparked on the flags of Dunguaire’s courtyard. A dozen baying hounds followed. In a hail of dust and gravel they rumbled through the castle gates and down the hill, swinging hard right at the bottom, in the direction of the village. The chase was on.

The retinue flew past the old castle arch in a blur and were up and through Stráid na Phuca, the main street of Kinvara. The thunder of hooves was such it rang the bell of St. Coman’s Church on passing. The reverberation shook the nave itself until it cracked from roof to foundation – a crack that can be seen to this very day. Some would tell you that for weeks later St. Coman’s bell rang of its own accord at the precise moment the troops flew past.

Onwards went the dishes

The few souls wandering the street ran for cover as a tsunami of wild and angry horsemen poured through the town, cloaks and crioses snapping like whips, a pack of baying hounds in their midst. If truth be told, the vision was an attractive kaleidoscope of colour, as the warriors were dressed in all their finery. Those garments, however, were not meant for such a test. The clasp flew off a wayward cloak and put a fine dent in Watson’s front door. The brass of a harness landed on Johnston’s roof and no less than six gold ties rolled in the dust by O’Deas. Beautiful, embossed, emblazoned and enameled adornments flew from the entourage in every direction. It was only by the grace of God no one was injured by flying finery. And then they were gone, without a ‘by your leave’ to the startled locals.

Onward also went the dishes, south-west like a swarm of swallows, bare specks against an azure sky. They soared between the forts of Ballybranigan, around Crushoa dolmen, and clipped the woods of Doorus. Thankfully they then swung inland in the direction of Parkliss Fort. If the dishes had flown over Doorus woods, the troop could well have lost them. Those woods were dense, dark and virtually impenetrable, containing trees as old as the land beneath their roots. They could confuse the best of warriors, trapping them for days, or allow a child to walk their breadth in the space of a morning. Existing in their own realm and at their own pace, Doorus woods were best left alone.

More than one curse was muttered

Their dinner had flown past Parkliss and dipped slightly at the bend of Corranrue Bay.

Guaire’s band turned in the wake of the dishes as a fine soft breeze joined them, carrying the whisper of the sea in its arms and two wild swans on its back. The birds bisected the air between hunters and prey, whistling nonsense to each other. Further ahead a pine marten threw a shape at crossing the bóthar, the track, in front of them. That creature is probably still there with the fright he got at the onslaught of horses and hounds. They paid no heed to the petrified creature. Their dinner had flown past Parkliss and dipped slightly at the bend of Corranrue Bay. The delicious scent of the dishes’ contents floated across on the breeze and up the nostrils of all who followed, adding insult to injury. More than one decent curse was muttered across the flanks of steeds as they negotiated passage through a copse of flowering blackthorn and whitethorn, scattering petals like snowflakes. Thorns as long as an infant’s finger grasped colourful threads from whirling cloaks. Stripes of crimson, purple and blue wool floated from the ends of boughs as they bounced back upon themselves in riotous indignation. The riders paid little notice as they climbed a small rise and broke through to the coast.

A cacophony of noise and feathers

At the shoreline, neither man nor beast had easy passage. The turf was soft and pitted with slippery clumps of sea grass and carraigín. The mud, and there was plenty of it, was deep and clinging, forcing horses and hounds to part like the prongs of a fork as they navigated the safest route between the tussocks. A clutch of emerald-headed mallard scattered from the ocean front. They rose in a cacophony of noise and feathers, leaving their females to crouch low among the gold-brown bladdered seaweed, safe but uncertain in their drab camouflage.

When the dishes reached the old ruins of Corranroo Castle by Aughinish Bay they turned left towards Corker Hill. It’s still one of the best places in Ireland to take the view. At its peak you can see where the Burren runs down towards the Atlantic, dissolving into stonewalled fields of lush pasture as it travels, with the odd cow here and there to finish the picture. Below that, Aughinish and Corranroo meld into Galway Bay, reflecting the clouds in its depths. Climíns of seaweed speckle the small harbours and seals rise and dip not far from shore, like dark commas among the gentle waves. The salt breeze from the Atlantic ripples the grass between, and if you pay heed, you can hear the cry of nesting falcons carry over the mountains as curlew herald warnings from the shore. Bide your time and you will feel the mountain ebb and flow to the rhythm of the ocean, drawing clouds across its brow to feed its stone cast hills and subterranean chambers. Eventually, in thunderous rapture, their waters explode between rocks and race towards the bay. And all the while you stand, battered, buffeted and mesmerised as the ocean below dances in harmony to the song of the Burren. Go mbeire muid beo ar an am seo arís.

Magic was afoot…

The view was lost on Guaire and his troops

The view was lost on Guaire and his troops. No one would blame them. They were warped with the hunger and no stomach was ever filled with a pretty sight. They got little respite either for, as with the shore, the hill proved hard going for man and beast. It was scattered with an abundance of small, loose rocks. And they were sharp. The grikes and clients, fissures and holes that are part and parcel of the Burren, are not meant for the chase. The dishes bore no such inconvenience, though they were having their own adventure far above. Kestrels and crows had noted their passing and the errant meal gathered followers by the minute – a wasted effort on their behalf. Magic was afoot and they had as little hope of acquiring a feast as the warriors beneath them.

High Tide

Onwards flew the victuals down the New Line, through Leagh, Funchin, Gortnaclough, over the bare limestone terraces of Oughtmama and around the side of Turlough Hill. Guaire’s horse clipped the edge of a loose slab and stumbled badly, nearly losing his seat on his Royal mount. With great difficulty man and beast righted themselves but the clasp of the King’s torc, his gold collar, caught in his cloak. It snapped under the strain and flew off over the rocks.

Despite this misfortune the chase was not halted. It was a sore loss to the poor man for it was a fine piece of craftsmanship – a relic even in his time, constructed with rare skill, forged from pure gold, with large circular bosses adorned with concentric circles and rope moulding along the body. There was weight in it too. Only shoulders as broad as a Kings could carry it with ease for a day. Some say that after it fell it was carried aloft by an eagle but soon proved an unsustainable burden to the creature and he dropped it at Gleninsheen.

The dishes finally slowed their flight

Kinvara, the Burren and beyond

At the base of Slievecarron a solid and familiar road greeted them. It was a track they often used for hunting and falconry and still bears the dent and ridge of many fulacht fiadh, or cooking places made and used during long nights on the mountain. On those nights, they’d set up camp by a spring. Depending on the weather they might construct a small shelter or sleep under the stars. Whatever way the mood would take them, one thing was sure, they always made an effort with their dinner.A good fire was lit and the catch of deer, boar or what have you, was prepared. Then they’d dig a rectangular pit in the ground, lining it with stone. With skins and vessels they’d fill the pit with water and bring to the boil by adding hot stones from the fire. Finally they’d pop in the meat and take their ease while the fulacht fiadh did the work for them. It must have been a fine feast, and doubtless even finer tales were shared in the heart of the mountain under a canopy of stars.

At the base of Slievecarron a solid and familiar road greeted them.

The King and his troops rounded the side of Slievecarron and headed into Kinallia. Up ahead, the dishes finally slowed their flight and dropped low over the rocks skimming a cluster of hazel and blackthorn at the base of the hill at Eagle’s Rock. The change in pace allowed King and retinue close the gap between them, giving blessed relief to horse and hound.

The silver ribbon of a spring. St Colman’s

The copse of trees was dense ahead but Guaire’s sharp eye picked the curve of a small path between the ferns with a silver ribbon of a spring nearby. Slightly to the left of its meander, he spotted the nave of a small stone church, nearly buried in the undergrowth.Further up the hill was the dark indentation of a cave, one of many on that fair mountain – this one with a well used track to its entrance. The King’s eyes glimpsed movement back towards the church. To its left, what he had thought to be a pair of rotted logs cast down by a Burren storm were, in fact, two human beings. Their shifts were a drab brown, their cloaks a muted green, their hair long and unkempt, their faces dark and weathered as the hazel around them. They appeared to be in prayer.That was Guaire’s first estimation of the scene before him. It didn’t take him long to realise that he was only partly right. One of the vagrants was offering supplications to the divine. The other was trying his best to assume the status of a tree, to avoid been seen. He looked terrified.

Sparks of light shimmered from blade, shield and bow

High on the hill. St Colman’s cave

And no wonder. Not only was an entire flotilla of floating plates descending in his direction from the heavens – an extraordinary sight in itself at the best of times – a retinue of heavily armed soldiers followed close behind, led by one with all the bearing and dignity of a king. As the young lad watched, the entourage fractured into smaller groups, swiftly and with purpose, forming a pincher movement at the base of the slope. Large and vicious swords were unsheathed. Bows were strung. Sparks of light shimmered from blade, shield and bow. Their aspect and determination made it painfully clear that even the most valiant attempt at escape was destined to fail. The poor servant thought either he was on his last legs and having visions before death took him, or he was in serious strife. Either way, his goose was cooked, as they say.

Not far from old Kinvara

One by one the vessels landed. The soup tureens found a fine spot for themselves directly in front of Colman. The bread settled itself nearby. Platters of meat rested slightly to their right, close by the stream. A couple of vessels clattered together as they sought safe landing. Space dwindled as vessels continued to alight. The honey had a fair old time of it trying to find safe purchase in a flat rock. Finally with a solid thump it buried itself in a bowl of hazelnuts, scattering more than a few. The cluster of nuts quickly reconfigured themselves around the invading vessel. At the end of it all, the arrangement of the wayward feast was such there could be no doubt the monk and his servant had something to do with it. And all the while the monk continued his prayers.

Man and beast were stuck fast

Colman’s fern

Guaire, had no idea the man before him was a close relation. Indeed no one could blame for that error. What knelt before him were two of the scruffiest articles he had ever seen in his kingdom. Indeed, they had the bearing of hags or sorcerers, neither of which was popular in Guaire’s kingdom.

“Beir greim orthu,” he ordered his troops. “Grab a hold of them.”

The troops were more than happy to oblige. Movement was made, or attempted at least. Nothing happened.

“Beir greim!” snapped the king, glancing at his men. He was met with faces locked in various stages of startled astonishment. The soldiers appeared to be struggling to dismount. Horses and hounds rocked to and fro on their legs. No human foot could touch the ground, hoof or paw could rise from it. Man and beast were stuck fast. His troops began to lower their weapons. But they were not capitulating in the face of so unworthy a foe. In point of fact, the weapons had become so heavy in their grasp the men were scarce able to hold them. One after another blades and bows scattered to the limestone beneath. Guaire too was stuck fast on the broad back of his mount. In turn the weight of his blade began to tell on his shoulder until it left his grasp and drew a halo of sparks out of the rocks below.

How did you get hold of my dinner?

The impact of Guaire’s sword on stone finally drew the monk from his trance. He raised his head and blinked against the sun, crossing himself as he completed his supplications. Then he paused, squinted upwards at the small army before him, and smiled in recognition of his cousin, Guaire.

“Dia duit mo Rí agus mo dhaoine uasal,” said he. “God be with you my King and noble folk.”

Colman rose from his knees to offer more formal welcome. Realising his path was blocked by a wealth of food, and excellent food at that, the monk blessed himself again, casting a smile of thanks towards the heavens.

“Cad is anim duit? Carbh as tú? Conas a chuir tú greim ar mo dinnéar?” the King asked. “What’s your name? Where are you from? How did you get a hold of my dinner?”

Troops and horses regained use of body and limb

Guaire was in no mood for pleasantries but Colman didn’t seem to notice. He strode forward. As he did, dish and plate moved up and around him, allowing him unhindered passage.

“Guaire, mo chara, mo clann! Failte! Táim an buioch duit an féasta seo a tabhair duinn. Buiochas le Dia ar do anam!”

“Guaire, my friend, my family! Welcome! I’m thankful for the fine feast you’ve given us. The blessings of God on your soul!”

Kinvara Sunset

The monk raised his hands in thanks to the King, and smiled. It was only then that Guaire recognised the face of his cousin through the lines of deprivation and suffering. In that moment the King was released from the grip of the horse. He quickly dismounted and clasped his cousin to his breast, simultaneously happy to see him, and horrified at the state of him. Truly, here was one among his people far more in need of food than he. Guaire realised, for the first time in this whole adventure it was not sorcery that called the dishes to flight. It was his own prayer, his offering to those in need. His supplication spurred the dishes upwards. Colman’s need and that of his young charge directed their passage. It was miraculous.

Seconds later, troops and horses regained use of body and limb. They dismounted and sheathed their weapons. They bowed to Colman, a little abruptly. It was with great difficulty they contained themselves, particularly as the food was still steaming, flinging scent so delectable it was almost obscene. The young servant looked like he was making an effort to eat the smoke as it drifted past.

Not long after he founded the monastery of Kilmacduagh

Blue Gentian – the Burren

Again, Colman proved his worth. He begged his King and retinue to join him in feasting. And they did. Well into the evening a King, his cousin, a servant and thirty troops broke bread together. No finer banquet was ever eaten on the Burren, taken as it was in the fresh air with the best sauce of all, hunger. Conversation was scarce for the first while, but as bellies began to fill, stories, laughter and song rose towards the mountain. The prayers, the flight, the chase and its conclusion were revisited in detail. The troops reflected on the kindness of their King and the holiness of his cousin, though on closer analysis, one or two among them would have preferred if the flight of the dishes had carried only enough sustenance for two. That way they might have remained at Dunguaire to watch the currach races across Kinvara Bay.

Guaire himself ate alongside Colman and discussed plans for him to set up his own monastery. Not long after, and with Guaire’s help, he founded the monastery of Kilmacduagh – a fine site, with a cluster of no less than seven churches set in fields of rolling pasture. The ruins of four are still easy to spot and the Abbot’s house rises high between them. St. Colman’s Cathedral sits by the graveyard where many souls both ancient and recent, have found eternal rest. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a n-anamnacha. Grand as it is, the Cathedral is dwarfed by the round tower that shares its situation. Indeed, the leaning tower of Kilmacduagh is well known to many – it’s the tallest in the country and still catches the breath of strangers who happen upon it.

He ate himself to death

He spotted the nave of a small church. St. Colman’s Church

It has been said that Colman’s servant was so hungry that, when he saw the food before him, he could not contain his appetite and he ate himself to death. Not far from the site of that famous feast a small protuberance can be found among the limestone rocks. It’s known as the grave of Colman’s servant. That’s what some would say. Others will tell you that the mound is a remnant of some ancient Burren dwelling. There may be some truth in that.

Bothar na Mias – The Road of the Dishes

The Flight of the Dishes led the warriors on a merry chase. The pursuit was marked by many, as was the trail they followed. The chase gave name to a Burren road, up by Kinallia. To this very day it’s called “Bothar na Mias” or the Road of the Dishes. A part of it bears the crescent shaped indents of hooves. It marks the spot where Guaire’s horse and those of his warriors stuck fast to the ground. Bothar na Mias covers some five miles, but time and tide and humankind has ruptured the trail in parts. For some, it is enough to know it is there. For those curious enough to seek, it can still be found.

The power of prayer was particularly potent

Kinvara, the Burren and beyond is marked by the magic of times past. Straid na Phuca (Street of the Ghosts), Kinvara has its own tales, as does Crushoa, Doorus and, indeed, each and every townland. Further south, Finn MacCumhall and his warriors left a grand selection of marks on a huge boulder near Ballysheen, where they sharpened their swords. Scattery Ireland bears the imprint of St Senan’s knees as he prayed dents in the stone – and that’s not the only place. He left his mark near the shore too. There are plenty more, but they are not the subject of this tale. That said, certain conclusions might be drawn from their existence – the warriors in those days were mighty strong, the power of prayer was particularly potent and the stone, rock and soil of Ireland made note of both.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page