Church at Kilmolash and Easter

Copyright: Arway Publications, 2022

In the west of County Waterford, Ireland, in a rural area known as Kilmolash, where it borders the townland of Woodstock, there stands an ancient stone church ruin. It is believed to have been laid out in the mid-7th Century A.D, according to some scholars of Irish history. This area moniker, Kilmolash, is derived from the adaption of the Irish language name of St. Molaise, or rather “Cill Molaise”, the church of St. Molaise. He lived from 566 to 639 A.D.

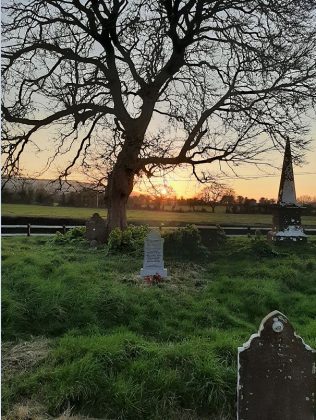

It is a wonderful structure and represents the stone masonry skills of the religious society of the time. It is situated on a rise at the intersection of two country roads. It also happens that this location is situated along the pilgrimage route of St. Declan. It is believed he passed by this exact position in the 5th century, on his way to Ardmore. Specifically speaking, the coordinates are: Longitude: 7° 48′ 34″ W; Latitude: 52° 6′ 16″ N.

I have come to know this church as I am situated nearby and have explored this church and surrounding hallowed grounds and graveyard of many of the local families. In my research of previous publications on this church, I have learned much of its possible building times, descriptions and potential meanings of the several inscriptions and carvings on these walls of stone.

In my many visits to this site, it has always intrigued me about how it was situated in this countryside. Why was it built in this location and even the actual alignment to the topography of the land and surroundings?

The church is only steps away from the River Finisk, which flows from the Blackwater, a major waterway of the area. Possibly, it was built here due to the access to clean water, as well as a travel route upon the Blackwater. Further, the land is fertile and open, lending itself to agriculture. So, maybe that could explain the “why here” question.

Looking at the structure, you notice the design features of the entry door, double bell tower, and several windows. There are several carvings, including a small 10cm Greek cross on the south wall corner. On the south side of the interior arch are faint carvings of the Christian Chi Pho and another Greek cross. The other carvings with them to the left and right are not discernable.

Another extremely interesting feature is the narrow ogee window opening in the upper front wall. It is situated in the center, at 255cm off the ground. The window framing is only 155cm tall and 70cm wide. The inner opening measures a mere 87cm high x 20cm wide.

The interior of the church does not suggest that there was a loft or other elevated interior floor. The peak roof was low and the stone walls do not show the signs of overhead floor supports. So why the window and why and ogee type? Sunlight perhaps? This does not seem likely. The window is in the front wall of the building and faces west, which reduces light to late day. It is quite slender, further limiting the amount of sunlight that would illuminate the interior.

If the ancient builders of the church could place the church in that location and in any position, why face it to the west and not another direction? This brought me back to more research of the church. I could not locate any explanation of its position or placement.

I took my compass into the interior and discovered that the front indeed faces west. It seems logical that the original alter area could have been along the interior of the original east facing wall. Standing against this eastern wall, the compass heading toward the window opening shows 265 degrees west. Only a few degrees away from 270 degrees, being due west. A few checks along the wall against the exterior side of the front wall stones confirms the heading. What is the significance of 270 degrees west? Glorious sunsets? Yes, but then what?

Spring. In Ireland, Spring is traditionally celebrated on 1 February, St. Brigid’s Day, the beginning of the planting season. The lunar spring however, the vernal equinox, is where the day and night times are equal. This usually occurs on either the 20th or 21st of March every year.

With the church being aligned nearly due west, what is the importance of this direction to this religious site? Going back to the time when it was built, both the Gregorian and Julian calendars were widely used. These methods of daily, monthly and yearly measurement were being debated by many astronomical scholars of the time.

Consequently, this caused many changes to the calendar. This flux of dating is significant to determining the timing and recognition of the holy times and dates as described in the bible. It could have been quite difficult for the clerics to rely on a calendar for times of religious observance. The phases and movements of the sun, moon and stars are a constant, even heaven sent, if you will.

Let’s get back to the naming of the area and church for a moment. Important to note is that this church is named after St. Molaise. Saint Molaise, also known as Molaise of Leighlin, is an abbot who lived into the mid-7th century. While in Rome, he became a proponent of the preferred doctrine concerning the timing of the precious events of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus.

On a side note, interestingly back then, the actual word “Easter” is not used to describe this religious event. It is not written in the bible. Its origin is uncertain, but it may have its roots in the Germanic word of Ostern, associated with renewal. Or developed from Eostre or Eostrae, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring and fertility.

The account of Jesus’ resurrection can be found in all four of the Gospels; Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Each gives a slightly different interpretation, but they all agree on the importance of the death and resurrection of Christ. The Old Testament reveals the observance of this time is coordinated with the Jewish Passover. Christians later adapted this timing to be the first Sunday, after the first full moon, after the vernal equinox (spring).

How would religious clergy of the 7th century know when to celebrate Easter? The answer lies with knowing when the vernal equinox occurs. How would they know that? By the rising and setting of the sun on those days of equal light and darkness of the lunar year. I opine that the architects of this church placed the forward-facing wall and entry of the church due west, then used the setting sun showing through a narrow window to shed light into the interior in a very predictable way.

The Kilmolash church, I propose, is positioned by these Gaelic-Irish Monks to precisely mark the vernal equinox. Once the first full moon after the equinox occurs, working from Christian teaching, the following days were for the crucifixion, Holy Saturday and the day of the resurrection, Easter.

Using the sun to mark significant periods of the year is nothing new. Just look at Newgrange. Built in the Neolithic period, it is positioned to mark the winter solstice, the shortest days of the year. To test my theory, I made observations on 19-23 March 2002, knowing that this was the period of the equinox. According to published charts, the vernal equinox for 2022 is 20 March at 3:33pm (first day of spring). On 19 March, at 5:20pm, sunlight coming through the ogee window shown on edge of north interior wall arch. A little later at 5:50pm, the light has moved farther in on the interior wall The sun then moved behind a tree at 6:05pm, obscuring the light from showing through the window. (Unfortunately, some of the setting sun is blocked by a large oak tree. No doubt it was not present 1600 years ago) At 6:20pm, as the sun comes from behind the tree, but a cloud bank covered the setting sun for rest of the day.

On 20 March, it was cloudy all afternoon, so no sunlight observations were possible. The same for 21 March, too cloudy. But, on 22 March, a partly cloudy day, sunlight is marked on rear wall at 6.10pm before the sun went behind a cloud bank.

The next day, 23 March, there was bright sunlight. The light is clearly marked on interior wall at 6.15pm. However, by 6.30pm, the sunlight has completely dissipated. It had moved too low on horizon to shine directly through window onto the rear interior of the church, as in the previous afternoons.

When viewing the positions of the sunlight on the interior wall, it is important to note that when the church was originally built, there was a rear wall where the arch is now. (This arch and subsequent anteroom was added around 1635 A.D.) And there was a roof. The light would have been closer in, more centered and brighter. The original interior is only 840cm long x 370cm wide.

With the 7th century calendar being in flux, there was a religious need to reliably determine the high holy season of Easter. My observations and measurements seem to support the notion that the church was deliberately positioned facing due west for that reason. Plus, the church is dedicated to Saint Molaise, an advocate of Papal doctrine of the timing of the crucifixion and resurrection, what we celebrate today as Easter. And not to be left out, is the fact that the church is set along the pathway of St. Declan’s Way, an already important religious ecclesiastic of God’s work.

Comments about this page

I had the pleasure of visiting this church ruin. It is so amazing to see the stonework. The narrow window does let the sun through in a very ethereal way. It was one of the highlights of my trip to Ireland. Thank you Art.

Art thank you for an excellent impressive, interesting article.

The images are wonderful…great that you discovered the light shining through window.

Add a comment about this page