Tá Oíche Shamhna beagnach ann! Hallowe’en is almost here!

Autumn, the season of the harvest, is nearly over and the darkness is drawing in – the short winter days are here. The dark winter season has traditionally been associated with death and the supernatural.

Here in the Museum at Turlough, we illustrate rural life in the last century, and much like today, people marked the calendar with communal events and celebrations. Their reliance on the land resulted in them being very much in tune with nature and the changing of seasons. Many of the festivals they celebrated were Christian but with more ancient roots and names.

The Quarter Days representing the start of the seasons were important festivals in the traditional calendar. Spring – February 1 (St. Brigid’s Day), summer – May 1 (Bealtaine), autumn – August 1 (Lúnasa) and winter – November 1 (Samhain).

Samhain marks the end of the harvest season

With many Irish festivals, the main focus became the eve beforehand. This is especially true of Hallowe’en which is celebrated on the night of October 31. Like many traditional celebrations, bonfires featured strongly, a tradition which has survived particularly in the larger towns and cities.

This festival marks the end of the harvest season, the word Samhain meaning the end of summer. All the crops of cereals, vegetables, fruit and nuts have been gathered for storage, to be used over the winter months. The abundance of these foods meant that they featured strongly in the festivities and fare. Potatoes were feasted on in the form of colcannon, boxty, dumplings and champ. Seasonal desserts were made with nuts, apples, and berries.

Children played games, using the apples and nuts they were given as gifts. Hallowe’en was also known as Snap Apple Night (Oíche na nÚll), Ducking Night, or Nut-Crack Night. Games with apples were very popular – they were either strung up or put in a bucket of water and retrieving them with your hands behind your back was a tough business! Another game involved each player taking turns to shave a slice away from a pyramid of flour or ashes, avoiding letting the fruit or stick fall from the apex.

If they chose the one with water, emigration was inevitable

The liminal times around the quarter days – an interstice between seasons, were favoured for divining what the future held. Marriage divination was especially popular and never more so than at Hallowe’en. A ring was often put into the colcannon or the traditional cake, the báirín breac, and whoever received the lucky slice was destined to be the next to marry. Other items to predict the future were sometimes put in the cake. These included a thimble (spinsterhood); a button (bachelorhood); a stick (to be beaten by the spouse); a rag (poverty); a coin (wealth) and a crucifix (the taking up of religious orders).

Another popular game played to foretell fate was to place four plates in front of a blindfolded person. If they chose the one with water, emigration was inevitable; grain indicated prosperity; clay foretold of death; a ring predicted marriage.

Blindfolded games were often used to determine the size and stature of the future spouse – one game involved selecting a cabbage and its size, shape and roots indicated the qualities of the husband to be.

A long single peeling of an apple skin thrown over the shoulder was examined to decipher the initials of the future spouse. The letters of the alphabet on pieces of paper left overnight in water might float to reveal a name. A snail left in a flour dusted bowl overnight, or on smoothed fire ashes, might reveal next morning a clue to the identity or the initials of a future husband or wife.

By putting objects under the pillow such as apples, cabbages, spade heads or spinning-wheel parts, the spouse might appear in a dream. Plants such as ivy and yarrow were also placed under the pillow to induce the dream. Hair and nail clippings put in the fire that evening were also believed to induce a dream of the partner to be.

Common dreams could feature the future spouse offering water or a towel if the dreamer had fasted before sleep or not dried their face!

There was a belief that evil spirits were about

The Christian feast days of All Saints on November 1 and All Souls on November 2, have created associated traditions surrounding Samhain. The word Hallowe’en derives from it being the feast of the Eve of All Saints also known as All Hallows Tide or Hollantide. The hallowed saints create the first part of the word and the second part comes from the word evening.

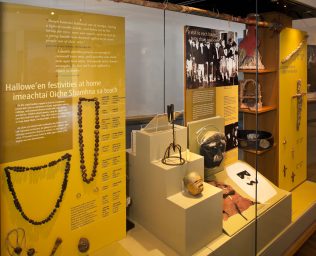

The association with winter and death in nature meant that there was much association with remembering those who had died and the protection of the home and family. Holy water was sprinkled on the inhabitants, around the threshold and other places within the home. Often, small wooden or straw crosses were made and hung to offer protection and luck for the coming winter and year (Four of the Halloween Crosses on display in the Museum Galleries are from Erris, Co. Mayo and another is from Letterfrack, Co. Galway).

This was also believed to offer protection from the fairies and other supernatural beings that were believed to be particularly active on this night. Another name for Halloween was Oíche na bPúcaí or Oíche na Sprideanna as there was a belief that evil spirits were about: people avoided travelling alone on this night for fear of abduction. Fairy mounds, trees or forts were avoided. Stories were told to children of the púca going about on this night spitting on the wild fruits. This was to try and prevent them from eating the damaged berries and apples after this date.

Anything that could be made to frighten people was used

People believed that on this night the spirits of the dead would be in limbo and would tend to travel around the country and return to their home place.

Halloween masks were made with this in mind to frighten the living daylights out of people (One of the scariest masks on display is one from An Fál Mór, Co. Mayo). Anything that could be made to frighten people was used. Turnips and potatoes were popular for turning into scary lanterns for walking with or placing on the windowsills. The pumpkin that is preferred today is an American development of this idea.

Guising – going from house to house in disguise – was always popular here. In the past adults, and later, children went from house to house entertaining and collecting money or treats for their own Halloween Party. These groups were known as guisers or vizards, coming from the masks that they wore to cover their faces. A traditional rhyme sung was:

Halloween knock a penny a stock,

If you don’t let us in we’ll knock, knock, knock,

If you haven’t got a penny a halfpenny will do,

If you haven’t got a halfpenny then God Bless you.

The Night of Mischief

Often it was a night to play dares on friends – visit a graveyard or ruin or some place with supernatural associations. Practical jokes were also played on unsuspecting neighbours. In Waterford, Halloween is called Oíche na hAimléise, ‘the Night of Mischief’. Tricks such as door-knocking and running were commonly played to scare those at home. Those who were out visiting might return home to find that their horse and cart had been taken apart and reassembled between a gate or even in the house!

Trick or Treat? Cleas nó Deas?

Clodagh Doyle is Keeper of the Irish Folklife Division National Museum of Ireland – Country Life

No Comments

Add a comment about this page