‘The wealth of the sea is proverbial, and even the weeds which grow in it are valuable and can be turned into money’, so began a letter in the Sligo Champion in 1915.¹ That an income and even a living could be gained from harvesting seaweed was well known before 1915. Seaweed had, and still has, many valuable uses. For tenants living in coastal areas where the soil was not as fertile as further inland, seaweed was a productive manure. Because of its high potash content, seaweed is suited to potash feeders, such as potatoes. In the often rocky and barren coastal fields, mixing seaweed with quantities of sand could literally create soil in which crops were grown to feed families.

Spreading seaweed by hand in a potato field in Cor na Rón Láir, Indreabhán, Co. Galway, 1967. © National Museum of Ireland.

The right to cut and gather seaweed was fiercely protected by landlords and contested by their tenantry. Regional newspapers frequently reported court cases where each side pressed their rights. Cases where the public rights won out against the perceived right of the landlord were celebrated. Taking on the cost of court and the ire of your landlord was calculated against the advantage of having access to a portion of seaweed rich shoreline. But securing rights was only the start of the work. Cutting and collecting seaweed could be a difficult and dangerous job. Tools were made locally to cut particular seaweed in particular environments.

Gathering seaweed with a racán ceilpe, a seaweed hook, Inis Oírr, Oileáin Árann, Co. Galway. © National Museum of Ireland.

On the Conamara coast, a seaweed drag or crook (called a crúca mór in Irish) was used for collecting seaweed from the rocks. In The Shores of Connemara, Maínis native Séamus Mac an Iomaire details the vast knowledge that coastal communities held in relation to seaweed, how productive each species was, when to cut them and what tools to use. Mac an Iomaire described a croisín as being sixteen feet long with a piece of wood, called a knife, across one end of it about eight inches long. The boat anchors above the seaweed and the croisín is thrust down and twisted until it is full of seaweed. When it is full, it is hauled up with about a stone weight of oarweed on the croisín.²

Seaweed hook or bacán, Inis Oírr, Co. Galway. © National Museum of Ireland.

A seaweed hook (scian mhór) that was also used off the Conamara coast was a scythe-like knife that was mounted on a twelve foot wooden handle and used from a boat to cut seaweed from rocks in deep water. The scian mhór had prongs on the back of the blade that helped to collect the weed. The Irish Folklife collection also holds a seaweed sickle (corrán mór) from An Spidéal, Co. Galway.

Seaweed pike from Corca Dhuibhne, Co. Kerry. The pike would have been fixed to a wooden handle. © National Museum of Ireland.

In the district of Tuosist in Co. Kerry, a corrán cam was a seaweed drag or hook that was mounted on a long wooden handle and used from a boat for cutting seaweed from underwater rocks. In Ard na Caithne, in the same county, a corrán feamainne was a forge-made slightly curved scythe-like blade mounted on a wooden handle about twelve feet long. It was used for cutting seaweed from a naomhóg. It is no longer used in that district. The corrán cam or sceanadóir that was used on Cléire, Co. Cork looked like a large scythe blade (62.5cm long) mounted on a long handle. Like the croisín, the corrán feamainne and the scian mhór, the sceanadóir was used from a boat out in the water.

Gathering armfuls of seaweed, Oileáin Árann, Co. Galway. © National Museum of Ireland.

Once cut, gathered and sorted, the heavy seaweed had to be transported to its final destination. One inventive method of delivering large quantities of seaweed at a time was to make a climín feamainne or seaweed bundle. Mac an Iomaire describes how a climín is constructed; ‘oars are laid out on the shore, a round heap of seaweed is made on top of them, and it’s tied with ropes, and when it floats it’s rafted with a long pole to its destination; normally the journey isn’t long’.³

A climín approaching the shore at Ros an Mhíl, Co. Galway, 1968. © National Museum of Ireland.

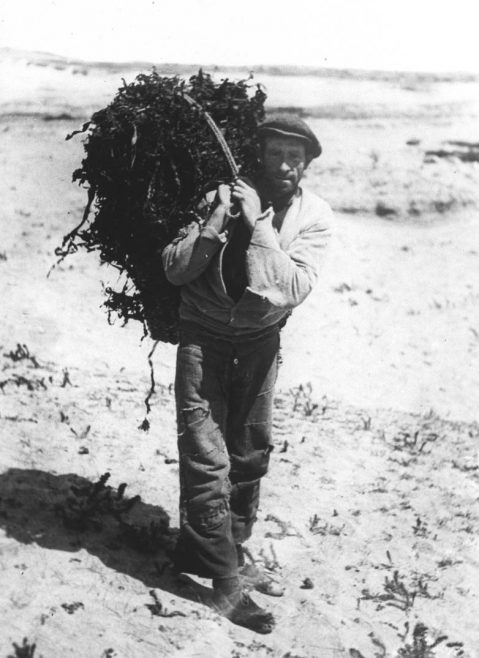

For an amount of seaweed that was too large for a practical climín or that had to travel greater distances, currachs and hookers were used to move the important crop. Smaller quantities were moved directly from the shore in baskets carried on the backs of men and women, as well as donkeys.

Bringing seaweed to Galway by hooker from Conamara, Co. Galway. © National Museum of Ireland.

Gathering seaweed, Oileáin Árann, Co. Galway. © National Museum of Ireland.

Ass loaded with seaweed for kelp, Oileáin Árann, Co. Galway. Seaweed was burned to make kelp. Kelp was used in many products such as soap. © National Museum of Ireland.

In Co. Donegal, a local seaweed gathering industry supplied the soap manufacturing industry in England.⁴ The difficult job of seaweed gathering as part of a local enterprise was filmed in Co. Clare in 1962 for an RTÉ News report broadcast and can be viewed here.⁵

Today, seaweed is still a much sought after commodity. Seaweed is used in many contemporary sectors such as biotechnology, cosmetics and biomedicine. These contemporary uses for seaweed are described in the Heritage Council publication Ireland’s Coastline Seaweed.⁶ The gathering of seaweed for gardening and horticulture is still practiced.

¹ Sligo Champion, April 24, 1915.

² Mac an Iomaire, Séamus, The Shores of Connemara, Galway: Tír Eolas, 2000, p.139.

³ Ibid. p.160.

⁴ “The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1048, Page 105” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

⁵ ‘New Industry Harvests Seaweed 1962’, RTÉ Archives.

⁶ Ireland’s Coastline Seaweed, The Heritage Council, 2008.

My thanks to Dúchas, RTÉ Archives and the Heritage Council.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page