Lesser Studied Emigration

Family ties

It has often been noted that Ireland’s greatest export has been its people. The phenomenon of Irish emigration has been long and has spread far and wide. Indeed, Coogan has stated in his extensive study on the world-wide Irish community Wherever Green Is Worn that the canvas of the Irish diaspora is so huge that no one book could attempt to describe fully the great outpouring.[1] It is estimated that in just more than one century since the act of Union until 1921 at least eight million men, women and children emigrated. As emigration was a big part of life for most generations in the nineteenth century it became a part of the expected cycle of life.[2]

Emigration for reasons of faith

The majority of the focus on emigration has, quite rightly, been on the millions who left Ireland’s shores to find a better life and escape economic stagnation, famine or persecution. However, another aspect of Irish emigration which has been relatively understudied in relation to these reasons is emigration for reasons of faith. Many Irishmen and women have travelled the world in order to, as they see it, spread the Christian word of God. And while waves of emigration for financial reasons tells the tail of Irish society for great numbers of ordinary Irish people, emigration for these religious reasons also says a lot about the Ireland of times past. The following extract is a small yet personal example of the type of emigration which has been an add-on to the wider picture of the world-wide Irish Diaspora.

They soon came under attack from German bombers

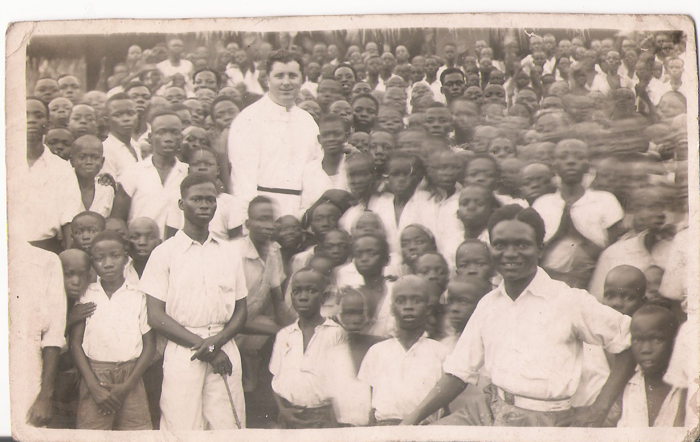

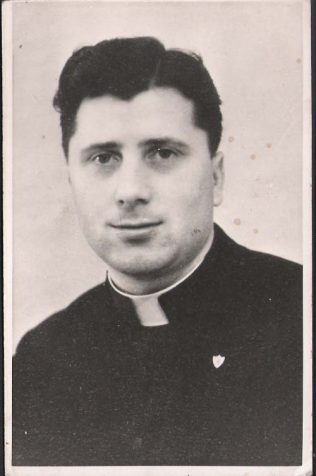

On April 13, 1914 John Francis Sheppard was born on Main Street in Cloughjordan Co. Tipperary, the eldest son of John and Bridget Sheppard. After studying in the local National School in Cloughjordan, John, or Jack as he was better known, moved on to Blackrock College in Dublin from 1927 to 1932. At Blackrock College he excelled academically and on the sports field. Upon finishing his studies in Blackrock, Jack entered the Holy Ghost Order in 1933, studying both philosophy and theology. Jack was then ordained on June 25, 1939 and soon found himself leaving Ireland with a group of missionaries for far off Africa at the beginning of 1940. The Second World War was at its height and travelling in international waters was not without its risks. The young missionaries were part of a large convoy of ships travelling to the African continent. They soon came under attack from German bombers, one of the ships was destroyed and sank while another was so badly damaged that it could not go on. However, the boat containing the missionaries escaped relatively unharmed and arrived at Lagos on the Nigerian coast. Here the group had to transfer to a smaller ship and travel a further 280miles to Port Harcourt before finally arriving at Onitsha where they were to fulfil their duties.

He was faced with many problems and dangers

The group were then dispersed to various parts to begin their mission. Fr. Sheppard was to be stationed in Onitsha. Here Jack was to begin the task of tending to the spiritual needs of 11,000 African Christians in a remote area where he was the only European for 20 miles in all directions. Already fluent in both Irish (he was a first cousin of Brendán MacAoire, a local Gaelic League activist in Cloughjordan) and English, in order to communicate effectively he obtained fluency in the language of the native people. While adopting many of the cultural practices of the native people he too shared some of his own passions with his parishioners, introducing football and traditional Irish music to the various villages under his charge. He was faced with many problems and dangers in his new country which he had to face head on. He reflected upon the remoteness of his location and the dangers involved his work in an interview given to the Nenagh Guardian in November 1946 when he returned home for short time:

“I got to know every bush path in the jungle as well as I know the roads around Cloughjordan. A short time before I left on vacation I had to cover 70 miles on a sick call, 35 out and the same back. Although I had a push bicycle, it was not easy work. The great enemy of the missionary is malaria. Southern Nigeria where I worked is reeking with it. Once bitten by the malarial mosquito, a man is liable to recurring attacks of the disease”.[3]

In the two centuries up to 1900, over 700 members of the Holy Ghost Order had died from malaria. Many more were to feel the recurring effects of the disease. And so it was with Jack, exposure to malaria was to effect his health on and off for the rest of his life. In 1957 he was on the move again, this time posted to Toronto, Canada and a teaching post in the Neil McNeil High School where he taught Maths and History. He was probably better known for his work outside of the classroom in his time in Canada. A lover of Irish culture he co-founded the Association of Irish Societies which brought Irish people of all backgrounds together to engage in recreational, cultural and humanitarian projects.

Most families in Ireland have an emigration story to tell

Jack’s exploits both in Africa and with members of his own diaspora in North America would go on to inspire his cousin Brendán MacAoire to take a similar path and join religious orders. The man who would go on to become Fr. Brendán MacAoire, born in 1910, was instrumental in organising community based events in his native Cloughjordan for those who were affected by the severe period of austerity in the 1950s. A co-founder of the Gaelic League branch in North Tipperary, Brendán organised classes, concerts and regular trips to the Gaeltacht, it provided a focus for people who were unable to emigrate during that period. While Brendán did not travel as far afield as Jack during his period in the priesthood (he only entered the priesthood at the age of 50), he took not only his spiritual message to Irish communities in various parts of England but also his passion for Irish culture and set up Gaelic League classes among those members of the Irish diaspora just as he had done in Tipperary.

As Tim Pat Coogan has rightly stated it is nearly impossible to quantify the great outpouring of Irish exiles around the world over several centuries of migration. Most families in Ireland have an emigration story to tell, and indeed there are many stories yet untold. This article has been intended as a personal recollection of members of my own extended family who have left these shores to make their mark on the world in their own particular way. Whether one is religious or not the practice of emigration for religious reasons remains very much a part of the wider story of the Irish diaspora and should be remembered as such.

[1] T.P. Coogan, Wherever Green Is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora (London, 2000) p. ix

[2] D. Fitzpatrick, Irish Emigration 1801-1921 (Dublin, 1990) p. 1

[3] Nenagh Guardian, November 9, 1946

No Comments

Add a comment about this page